Section five | Cities

Introduction

By 2050, two-thirds of the global population will live in cities, and over 70% of the global demand for infrastructure over the next 15 years is expected to be in urban areas.1

This means that how cities develop is important both for growth and for climate change. The Sustainable Development Goals recognise the centrality of future urban development to achieving sustainability goals, in setting out Goal 11 to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

Given the rapidity of urbanisation and the long-lived nature of urban infrastructure, the decisions made today by national and city decision makers – in partnership with private investors – will determine our economic future and climate security for the second half of the century. According to recent research, the urban infrastructure investment decisions taken just over the next five years will determine up to a third of remaining global carbon budget.2

With growing numbers of poor people now concentrated in urban and peri-urban areas, investment in better urban infrastructure – designed to meet the needs of the poor – can also offer huge resilience dividends. This includes providing access to electricity and clean water, alongside of building schools and health clinics where the broader benefits of a sustainable infrastructure agenda include helping to keep children healthy and in school while building better livelihoods for their parents. Sanitation systems and sewers also build resilience, because during floods, lack of adequate sanitation is closely linked to disease outbreaks. Public transit, district heating and building efficiency also all have poverty reduction benefits for the poor because they increase access and reduce costs of services to the poor, while also providing global benefits by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and future climate risk. Finally, improved flood management systems build resilience for all, but will disproportionately benefit the most vulnerable populations, including the urban poor who often settle in flood plains. Getting infrastructure right in cities is fundamental if we are to build future prosperity, reduce poverty, strengthen resilience to climate change and extreme events and reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pollution.

Why urban infrastructure needs to be sustainable

In many countries, urban development has followed a sprawling, inefficient model that leads to congestion, car-dependency, high resource use and high GHG emissions. Yet an alternative is starting to emerge – one focused on compact, connected and sustainable urban growth to create cities that are economically dynamic, vibrant and healthy. Such cities are more productive, socially inclusive and resilient, as well as cleaner, quieter and safer. It is a win-win for the economy, the people and the environment.

Investing in sustainable urban infrastructure that supports compact, connected, resilient and sustainable growth in cities could yield high returns on multiple levels:

- Compact urban development could reduce global urban infrastructure requirements by more than US$3 trillion from 2015 to 2030, and favour public transport over dependence on personal motorized transportation, which in turn limits GHG emissions and improves local air quality.3

- Investing in public transport, building efficiency and better waste management could save cities around US$17 trillion globally by 2050 (based on energy savings alone) and further reduce emissions and build resilience.4

By contrast, development through sprawl raises the costs of infrastructure and consumer goods, needlessly emits GHGs, and contributes to unsafe roads and poor health. Sprawl is estimated to cost the US economy alone more than US$1 trillion every year.5

Building urban resilience is complex, particularly for rapidly growing cities but it is increasingly part of the agenda for cities around the globe. The more resilient a city is to shocks and stresses, the greater the likelihood that the city will “bounce back” to its normal state and citizens will resume their lives and livelihoods with the least loss to property and life.6 Cities can increase their resilience each time a shock or stressor affects them by “building back better” to be more prepared for future events. Low income countries in particular are facing the challenge of pursuing development pathways (including substantial investment in infrastructure) while facing growing adverse impacts of climate change. Ensuring that investment in infrastructure takes climate change risk into account, including higher risk from natural hazards such as extreme temperatures, floods and droughts, will determine its sustainability. On the other hand, poorly constructed infrastructure in rapidly urbanising areas intensifies climate risks and vulnerability to climate impacts.

Many cities are also working hard at sharing what has worked and what has not, and learning from each other. For instance, Rotterdam is helping city officials in Ho Chi Minh City, which is topographically similar, create and implement a Climate Adaptation Strategy through the Connecting Delta Cities Network and develop financial resources and technical capacity.7 Global networks like the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, the Connecting Delta Cities Network and CityLinks can play a major role in this.

Demand for sustainable urban infrastructure

The expected rapid growth in urban population will be most pronounced in emerging and developing countries, along with expected growth in economic output, energy consumption and carbon emissions. This growth will be led by large and fast-developing cities in emerging and developing economies, particularly in China, India, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Rapid urbanisation will create significant demand for infrastructure and in urban areas, where the local benefits are near-term and visible, there is demand to make that infrastructure sustainable. Urban infrastructure investment is expected to make up roughly two thirds of the total investments in infrastructure to 2030, about US$4.1–4.3 trillion per year.8

These estimates still do not consider the investments needed to adapt urban infrastructure to climate risks, which is crucial. With their dense populations and, particularly in developing countries, often large clusters of people living in marginal areas, cities are highly vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather events. The risks are especially great for the 75% of the world’s large cities that lie on a coastline and are thus exposed to sea-level rise and storm surges.9 Estimates of capital costs required for urban infrastructure adaptation range from US$11–20 billion per year,10 to as much as US$120 billion per year by 2025–2030,11 indicating deep uncertainty on the numbers.

The supply of urban infrastructure finance

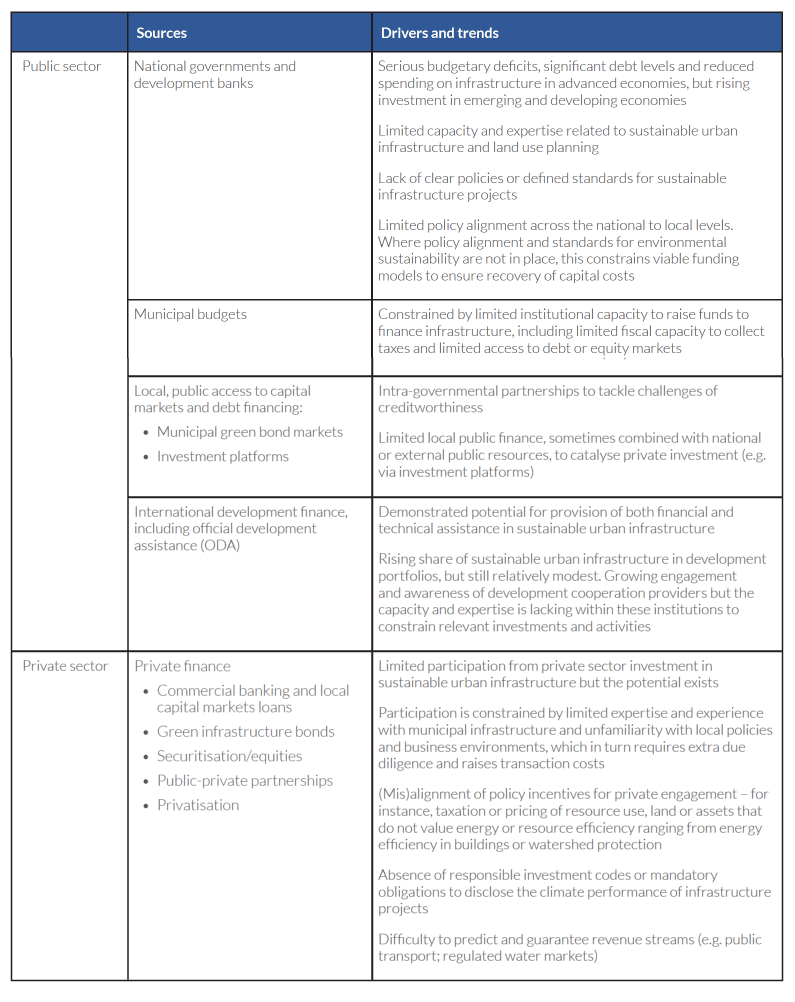

Despite the critical importance of infrastructure for urban development, financing smarter, more sustainable urban infrastructure remains an immense challenge, particularly in emerging and developing economies, and particularly when it comes to large-scale projects. Competitiveness, population and business growth, and public safety drive infrastructure finance demand, though the sources of finance vary as do the specific trends that shape its supply.

Finance for sustainable urban infrastructure is hindered by many of the same barriers faced by sustainable infrastructure in general, including market failures, short-term thinking, and a lack of bankable projects and capacity at the urban level to prepare projects. Many cities around the world are constrained in their ability to retain local revenue sources, take on debt, invest in major projects and engage in public-private partnerships. Many projects are also hampered by the fact that they involve public goods. The scale of the capital investments – especially for transport systems such as bus rapid transit (BRT), light rail, and underground rail systems – often far exceeds the ability of national and local governments. However, when public capacity to partner with the private sector is in place, public financing can crowd in private finance and investment and enabling conditions can incentivise it. In developing countries, international development finance can play a key role.

There are also financing challenges that are specific to urban infrastructure (see Table 4). National and local policies may not always be aligned, creating conflicts and, for investors, regulatory uncertainty. Cities often have limited capacity to plan, budget, and ability to secure finance for, and oversee such large projects. As indicated in the sub-sections that follow, a number of opportunities exist to address these challenges.

The Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative

The Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative